The United States is tracking a Venezuela-linked oil tanker that has avoided capture for several days as officials consider using additional Coast Guard assets to seize it. The tanker, known as Bella 1, has refused boarding requests, forcing the Coast Guard to wait for specially trained teams and highlighting both tougher enforcement of sanctions near Venezuela and the agency’s limited resources for such operations.

A tense pursuit at sea

The pursuit of the tanker began earlier this week and has stretched on for several days in waters near Venezuela. The ship is suspected of being part of a “dark fleet,” a term used for vessels that deliberately hide their movements to evade international sanctions. These ships often switch off tracking systems, change names, or operate under unclear ownership to stay out of sight.

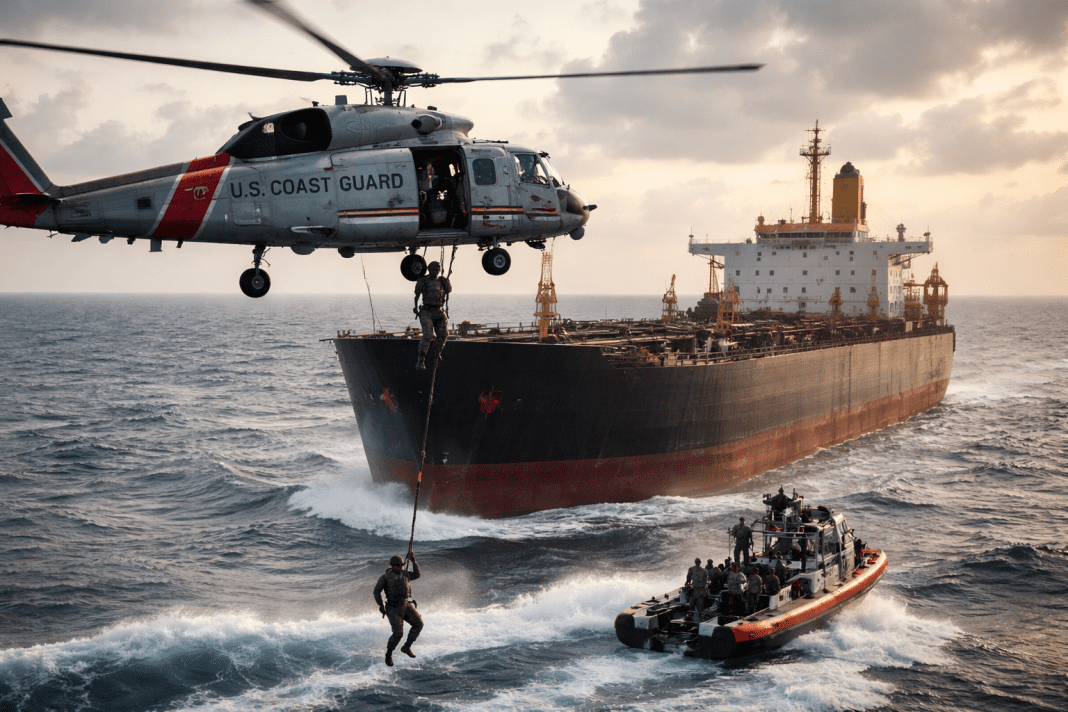

In this case, the tanker has repeatedly refused the Coast Guard’s requests to board. This refusal has made the operation far more difficult. Coast Guard crews can usually board vessels during standard inspections, but when a ship refuses, authorities must carry out a forced boarding using highly trained specialist teams.

Only a small number of these elite teams operate worldwide. They train for dangerous missions, including being lowered from helicopters onto moving ships. Because agencies deploy these teams across wide regions, they are not always available to respond immediately.

Officials said that when the pursuit began, the nearest trained team was located far from the tanker’s position. As a result, the Coast Guard has continued to monitor and follow the vessel while waiting for the necessary personnel and equipment to reach the area.

Despite the delay, the White House has said the United States remains in active pursuit of the tanker, linking it to Venezuela’s efforts to bypass sanctions. Officials have also noted that boarding and seizing the vessel remains possible but is not guaranteed.

Why the Coast Guard is leading the operation

Unlike the U.S. Navy, the Coast Guard has the legal power to enforce laws at sea, including stopping, boarding, and seizing ships suspected of breaking U.S. sanctions. Because of this authority, it leads efforts against sanctioned oil tankers operating near Venezuela.

Earlier this month, U.S. policy tightened further as the administration ordered a broad crackdown on sanctioned oil shipments entering or leaving Venezuelan waters. In recent weeks, the Coast Guard has already seized two tankers in the region, using helicopters and armed boarding teams in high-risk operations.

The pursuit of the tanker Bella 1 has been more difficult due to distance, timing, and limited access to specialized teams. While the U.S. military maintains a strong presence in the Caribbean, the Coast Guard has fewer assets, making the gap between enforcement goals and operational capacity more visible.

Limited resources under growing strain

The situation has renewed attention on long-standing concerns about the U.S. Coast Guard’s readiness. The Coast Guard serves as one of the nation’s armed services, operates under the Department of Homeland Security, and handles a wide range of missions at the same time. These duties include search and rescue, drug interdiction, migrant operations, environmental protection, and maritime law enforcement.

For years, officials have warned that the service faces heavy strain. A growing workload, along with aging ships and aircraft and persistent staffing shortages, has made it harder for the Coast Guard to respond quickly to complex and high-risk missions, including seizing oil tankers that refuse to cooperate.

The strain becomes even clearer when compared with the broader U.S. military presence in the Caribbean. While the United States has deployed aircraft carriers, fighter jets, and other warships to the region, the Coast Guard operates with far fewer dedicated assets. Its ships and aircraft often juggle multiple assignments, which limits commanders’ flexibility during fast-moving situations.

Despite these challenges, the Coast Guard continues to play a major role in national security. In recent months, it has reported major drug seizures in the Pacific, removing tens of thousands of pounds of illegal narcotics from circulation. These operations demonstrate both the service’s effectiveness and the heavy demands placed upon it.

Officials have described the Coast Guard’s condition as a readiness crisis that has developed over decades. Although Congress has approved additional funding, experts say the service needs time to improve training, equipment, and staffing levels. The ongoing tanker pursuit shows the real-world pressure of enforcing sanctions at sea when resources are limited and targets actively resist.